skynesher / Getty Images

More Can Be Done to Increase Representation of Feds with Disabilities

A new report shows people with disabilities make up a greater percentage of the federal workforce, but those employees are less likely to be in leadership roles and more likely to leave their jobs.

Although some progress has been made, more can be done to increase representation of individuals with disabilities in the federal workforce, according to a new report.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission released a report on Thursday that establishes a baseline to measure the effects of a final rule issued at the tail end of the Obama administration as well as to assess trends for federal employees with disabilities.

“The EEOC is delighted to see that our support of people with disabilities has borne fruit in so many ways,” said Carlton Hadden, director of the EEOC’s Office of Federal Operations in a press release. “Clearly, though, more progress is needed. The EEOC will continue to work to advance the opportunities and well-being for this still too underutilized and underappreciated segment of our population.”

The Current Situation

Hiring individuals with disabilities for permanent positions has been an ongoing challenge for most civilian federal agencies.

In fiscal 2018, “among permanent hires, the federal government exceeded its 2% goal for hiring of [persons with targeted disabilities], (2.36% of permanent appointments), but agencies failed to meet the 12% goal for [persons with disabilities], (11.20%),” as set by the 2017 rule, said the report.

“Targeted disabilities” are specific types of disabilities that the federal government determined are the most serious and are affiliated with fewer employment outcomes, Karen Brummond, social science research analyst in the EEOC’s Office of Federal Operations, told Government Executive.

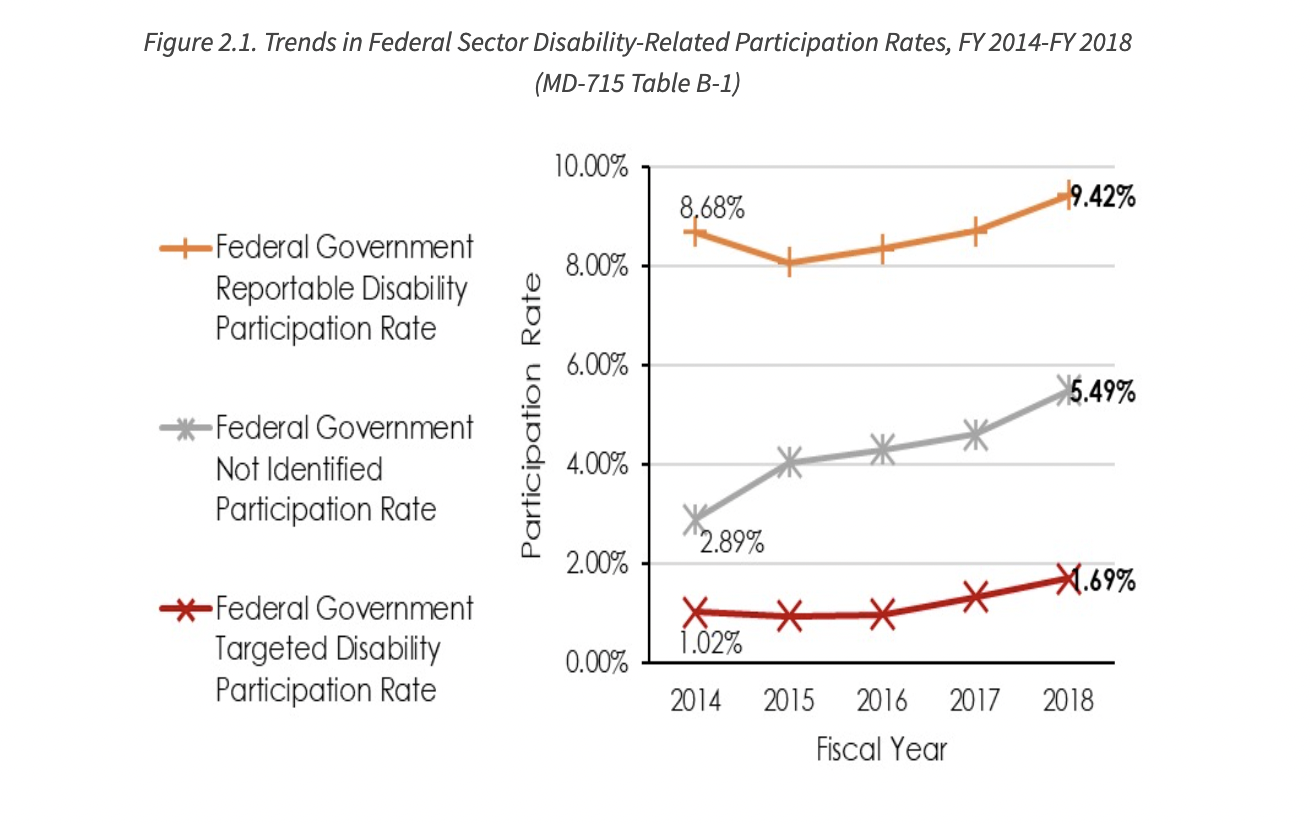

Overall, however, the number of federal employees with disabilities did increase from fiscal 2014 to fiscal 2018 as shown below.

While representation of individuals with disabilities and targeted disabilities is increasing, they were less likely to hold leadership roles than those who did not identify as having a disability, the EEOC found.

About 16% of federal employees without disabilities were in leadership roles in fiscal 2018 compared to about 10% of federal employees with targeted disabilities and 13% of federal employees with disabilities overall. However, those with disabilities “were promoted at a rate similar to what would be expected based on their participation rate,” said the report.

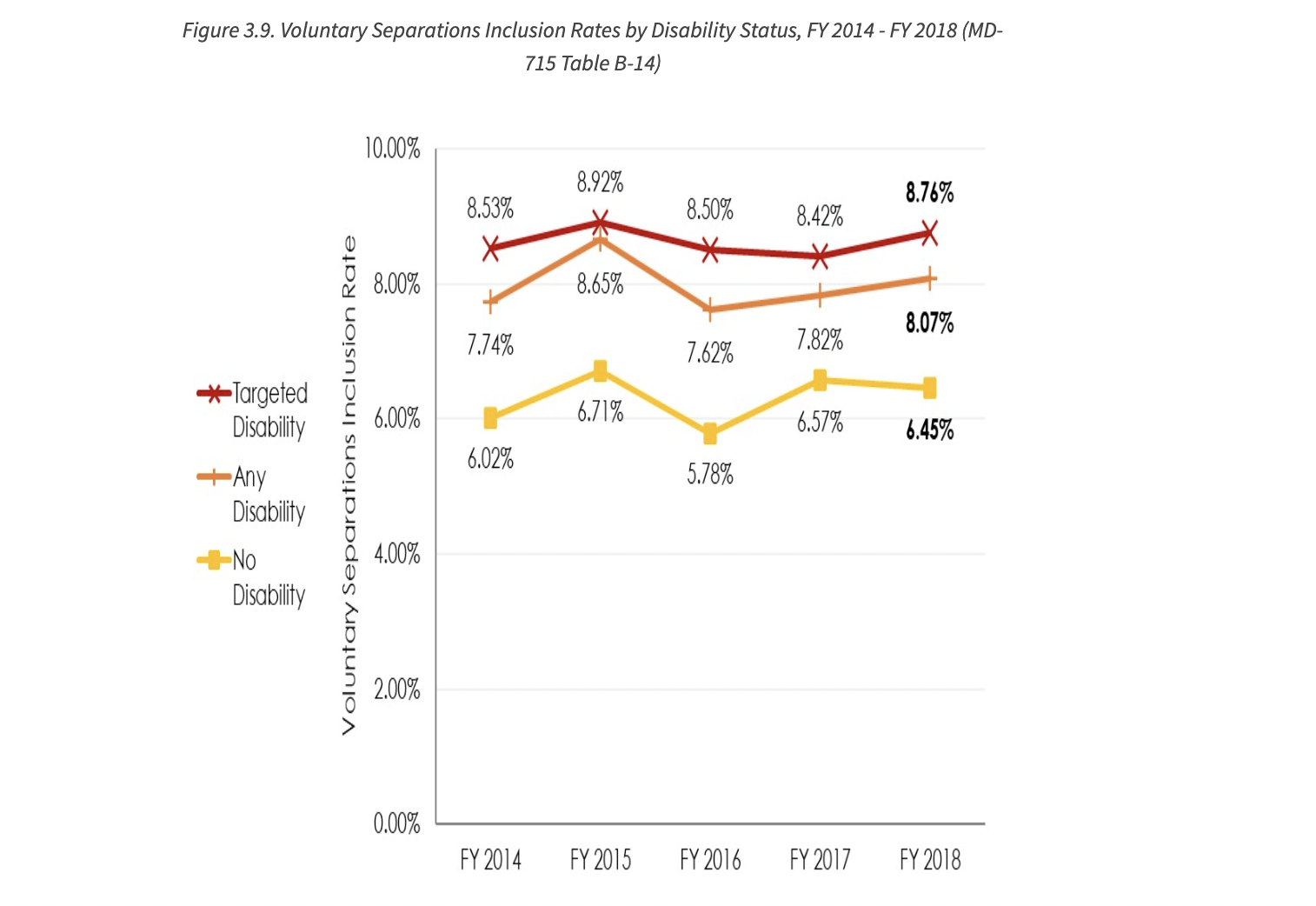

Separations from federal employment––both voluntary and involuntary––have been another pervasive issue facing the disabled community.

“[People with targeted disabilities] were the most likely to separate from federal employment, and [people with disabilities] were more likely to separate than persons without disabilities,” said the report. The Government Accountability also looked at this in a report issued in June 2020.

“There’s something wrong with this picture when so many more people with disabilities leave the government than those without,” Hadden said. “Our government needs to be the best workplace it can be for everyone.”

The number of formal EEO complaints in the federal sector that alleged discrimination based on physical disability and mental disability increased by about 22% and 72%, respectively, from fiscal 2014 to 2018. This “may be due to increased discrimination against persons with disabilities or increased comfort with filing an EEO complaint among persons with disabilities,” said a press release from the EEOC.

The expansion of telework due to the COVID-19 pandemic provided an automatic reasonable accommodation for individuals with disabilities, but with the reentry process some individuals might now have to request that accommodation, which “may result in increased discrimination complaints if they are not granted telework,” Brummond said, based on her speculation.

When asked why the data was not more current than fiscal 2018, Brummond said these reports often take time, “however we believe that the conclusions to this report still hold” in comparison to some data from more recent years.

Recommendations Going Forward

Based on the findings, the EEOC made six recommendations to federal agencies to improve their insight into their employees with disabilities and targeted disabilities as well as improve their hiring and retention practices and meeting of accommodation requests.

In 2010, President Obama set a goal to hire 100,000 disabled individuals across the federal government, which was similar to an unfulfilled pledge from President Clinton. OPM announced in October 2016 that the Obama administration exceeded that goal by hiring almost 110,000 disabled employees between fiscal years 2011 and 2015. The percentage of employees with disabilities in OPM’s report differs from EEOC’s numbers because EEOC’s report included the U.S. Postal Service, Tennessee Valley Authority and a few other agencies, Brummond explained to Government Executive.

Under the Trump administration, dozens of Democratic lawmakers raised concerns in June 2019 about the federal government falling short of its goals to hire more employees with targeted disabilities and accused Trump administration officials of firing disabled workers at a disproportionately higher rate than those without disabilities.

Then in June 2021, President Biden issued an executive order on increasing diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility in the federal workforce, which aligns with other, related initiatives by his administration.

Brummond said this was the first time she saw the “A” for “accessibility” in “DEIA” and thinks it “will improve the workplace for persons with disabilities broadly.”

Additionally, OPM’s strategic plan for fiscal 2022-2023 says it seeks to increase the number of employees with disabilities/targeted disabilities by 5% by Sept. 30, 2023 as well as look at the possible barriers for employees with disabilities to advance in the federal workforce (including reaching the Senior Executive Service) and develop plans to get rid of those hurdles.