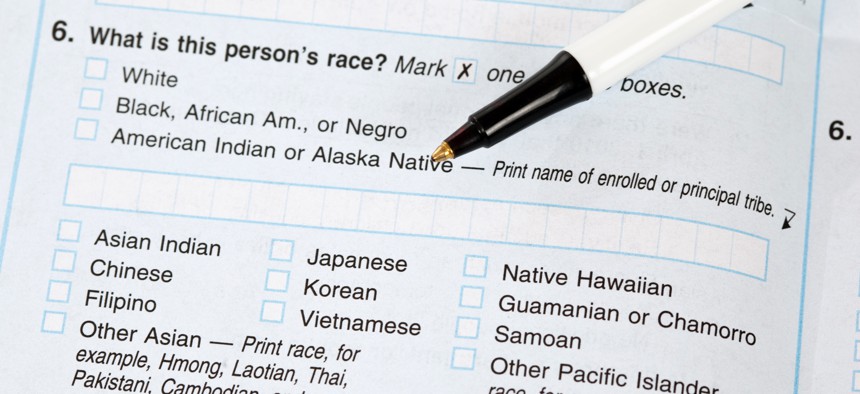

The Office of Management and Budget is updating the federal government’s data standards on race and ethnicity for the first time since 1997 to better reflect respondents' feedback. blackwaterimages / GETTY IMAGES

Biden administration finalizes first demographics data standards update in nearly 30 years

No longer will “race” and “ethnicity” be bifurcated into separate questions in federal datasets and questionnaires such as the U.S. Census, and people of Middle Eastern or North African ancestry will have their own distinct category.

The Biden administration on Thursday finalized the first update to how the federal government collects data on race and ethnicity since 1997, at once both simplifying the process and increasing the granularity of results.

The Office of Management and Budget first began the process of updating the standards for the government’s data on race and ethnicity in 2022, citing respondents’ longstanding frustration with outdated terminology and identity options that did not align with their own experiences. The federal government first developed the data standards in the 1970s, as agencies sought ways to enforce civil rights laws, and prior to this week, was updated only once in 1997.

As part of the update process, OMB convened a working group of agency experts, solicited more than 20,000 public comments and conducted dozens of listening sessions both in person and virtually. The resulting standards update, which is scheduled for publication in the Federal Register Friday, takes immediate effect for new data collection efforts, while agencies have until 2029 to update existing surveys and government forms to reflect the new rules and categories on existing programs. That 2029 deadline means that the 2030 U.S. Census will be governed by the new standards as well.

So what’s changing? For one, the government will no longer ask separate questions regarding a respondent’s race and ethnicity, instead incorporating “Hispanic or Latino” as part of the core list of “race and/or ethnicity” categories. Splitting survey responses regarding people’s race and ethnicities had become a headache for agencies and respondents alike, OMB wrote.

“The working group’s final report states that ‘since 1980, responses to the decennial census in each subsequent decade have shown increasing non-response to the race question, confusion and concern from the public about separate questions on ethnicity and race,’” OMB wrote. “Results from the 2020 Census showed that 43.5% of those who self-identified as Hispanic or Latino either did not report a race or were classified as ‘Some Other Race’ alone (over 23 million people.)’ This increasing non-response and reporting of SOR was one of the primary indicators to OMB that [the existing data standard] was no longer providing options that align with how respondents prefer to identify.”

And a new addition to the list of races and ethnicities available for self-reporting in surveys and on government forms is “Middle Eastern or North African.” Previously considered part of the “White” reporting category, the 1997 standards have become out of sync with how most Middle Eastern or North African respondents viewed their own racial or ethnic identity.

Additionally, OMB is updating the actual wording of questions on race and ethnicity to better encourage respondents to select multiple categories if they come from a multiracial or multicultural background. And it is removing a number of antiquated phrases from the definitions of the main categories, such as “Negro” from the Black or African American definition, “Far East” from the Asian definition, as well as “who maintain tribal affiliation or community attachment” from the definition for American Indian or Alaska Native.

OMB said it plans to continue to monitor respondent satisfaction and conduct additional research as part of an effort to update definitions more frequently to keep pace with public consensus on identity.

“In regards to [the working group’s] recommendation, OMB does not include the phrase, ‘Note, you may report more than one group’ in the required question instructions,” OMB wrote. “Additional testing conducted after the working group delivered their final recommendations found that including this phrase had the opposite of the intended effect and resulted in a sizeable decrease in the number of respondents selecting multiple responses.”

Federal agencies will have 18 months to develop action plans to govern the implementation of the new data standards, though, when possible, OMB encouraged them to implement the changes “wherever possible” prior to the deadline.

“Based on input from federal agencies, the deadline for compliance with this revised [data standard] is five years after the publication of this notice,” OMB wrote. “[Most] programs will be able to, and should, implement revisions sooner than the five-year deadline for compliance. Certain programs that involve interconnected data across multiple agencies or offices, or that rely on data collected and provided by non-federal entities, may take longer to implement than programs like statistical surveys, but all programs are required to bring their collections into compliance within the five-year implementation period.”