Members and supporters of the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) participate in a "Stand Up, Stand In" protest in the Hart Senate Office Building atrium in Washington, D.C., as part of the 2020 Legislative and Grassroots Mobilization Conference. Sarah Silbiger/Getty Image

State of the Unions: A New Normal

After nearly four years of drag-out fights with the Trump administration, President Biden pitched himself as a willing partner to federal employee unions. How have the government and unions navigated the transition to this new approach?

The last six years have been something of a roller coaster for federal employee unions.

The election of Donald Trump as president in 2016 helped to spark a wave of federal workers becoming dues-paying union members, over fears that a Republican administration would make cuts to pay and benefits and chip away at their civil service protections. Those fears came to fruition in 2018, as Trump rolled out a series of executive orders making it easier to fire federal workers and clamping down on unions’ role at federal agencies.

Those edicts deeply curtailed union representatives’ access to official time, evicted unions from federal office space, limited feds’ ability to pursue grievances and curtailed the topics unions could bargain over during contract negotiations. Unions then spent the next two years first challenging the executive orders’ legality, and then their implementation before independent agencies like the Federal Labor Relations Authority and Federal Service Impasses Panel, both of which were controlled by Trump appointees hostile to organized labor.

But the inauguration of President Biden, who campaigned in part on respect for government experts and the federal workforce, in 2021 marked a 180-degree turn for federal labor policy. Biden swiftly rescinded Trump’s workforce executive orders, including the former president’s abortive effort to strip tens of thousands of federal workers in policy positions of their civil service positions through a new job classification called Schedule F. Biden also created task forces focused on federal worker safety during the COVID-19 pandemic and recommending improvements to labor-management relations at federal agencies, and he instructed agencies to expand the scope of collective bargaining.

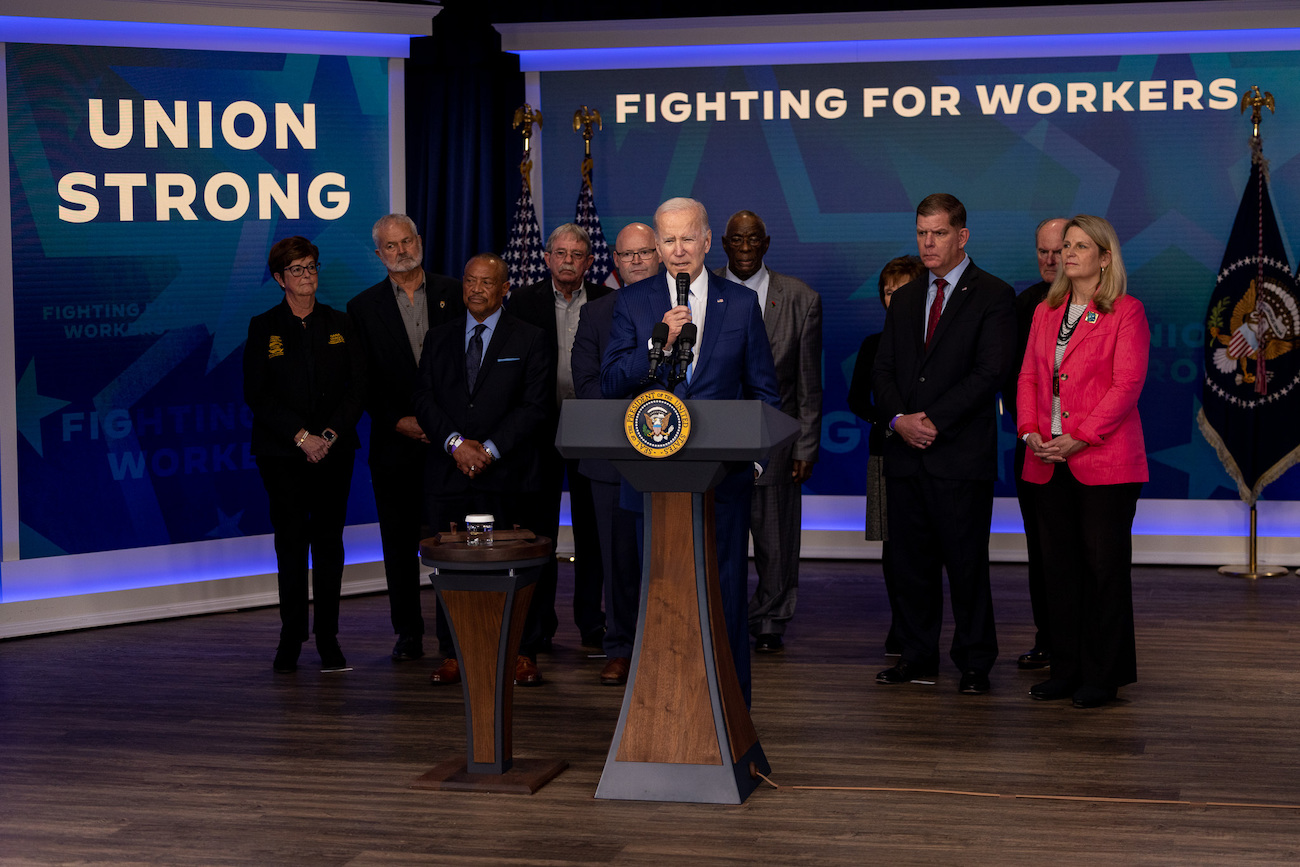

Biden’s focus on workforce issues prompted federal employee union leaders to laud him as “the most pro-labor president” in recent memory. But how did the administration’s edicts actually play out on the ground?

‘Almost the Polar Opposite’

That’s how Tony Reardon, national president of the National Treasury Employees Union, described his experience with agency officials over the last two years.

“My old standby when I talk about this is [the Health and Human Services Department], because HHS was our poster child, really, for how the last administration dealt with collective bargaining,” Reardon said. “We had, as I recall, 16 weeks scheduled as part of our ground rules for bargaining [during the last administration], and it was after one or two days that they declared an impasse and wouldn’t come and describe their proposals and they wouldn’t even meet with our team. It was an environment that was clearly created by the administration and management folks not interested in working with their unions.”

But since Biden took office, he’s seen a sea change at the department: HHS reinstituted its labor-management forum, and the union and management are back at the negotiating table on a new collective bargaining agreement. And similar changes have taken hold at other agencies where NTEU represents employees, like the Internal Revenue Service and U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Matt Biggs, president of the International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers, said that although he has encountered pockets of resistance within some agencies’ labor relations offices, the Office of Personnel Management, which was briefly slated for abolition during the Trump administration, has stepped up in a big way.

“OPM has been very aggressive in encouraging these agencies to follow the lead of the worker empowerment task force, and to sit down and bargain in good faith with unions,” Biggs said. “There are still challenges in some places, and there are still anti-union managers embedded in some of these different agencies, but it’s been very successful with our union, anyway.”

Biggs described OPM’s proactivity as a new phenomenon, perhaps related to the agency’s embrace of a report from the National Academy of Public Administration, which called for the HR agency to focus less on ensuring transactional compliance with regulations by agencies and more on becoming a governmentwide leader on human capital issues.

“It’s just different. You can compare it to the Obama and Clinton administrations,” he said. “In previous administrations, they might have said some of the right things, but this Biden administration OPM has actually kind of walked the walk. When there are issues at agencies, at least when it comes to IFPTE, OPM is willing to pick up the phone, contact the agencies, and correct, or at least mediate things, to reach some sort of resolution.

Biggs and Reardon both specifically cited OPM Director Kiran Ahuja and Deputy Director Rob Shriver as critical in this regard.

“To be fair, it’s not only OPM, but clearly whether you’re talking to Rob or to Kiran, or to Tim [Soltis, a senior advisor at the Office of Management and Budget], I think those folks play an active role in making sure agencies understand what the administration’s position is on certain things,” Reardon said. “So when we come up—and we certainly have—against an agency that really doesn’t want to talk to us about things predecisionally, or maybe they’re not really all that interested in providing the data that the White House task force on organizing requires them, they can play a really helpful role.”

American Federation of Government Employees National President Everett Kelley described the Biden administration as a “life raft” after years of fighting for survival under the last administration. Pain points remain, however, particularly at agencies like the Social Security Administration and the Veterans Affairs Department. At the VA, he said his union has been negotiating with management for over a year on a new contract, but have yet to reach a deal.

“We haven’t gotten everything we’ve wanted, of course, but it’s been much better,” he said. “Management has been meeting with us and talking with us and we’re back at the work sites and able to talk to and represent our members. But there are still some issues where maybe there are some Trump holdovers where maybe we have some problems.”

Reardon described some agencies’ hesitance to adopt more collaborative relationships with their union partners as rooted in a natural desire to maintain a preexisting power dynamic.

“Let’s face it: I think that oftentimes when agencies feel, and I don’t want to get into which individual agencies on this, if they feel the rules are leaning in [employees’] direction, they will be willing to act sometimes a little more to the benefit of employees or their unions, but they kind of like having the upper hand,” he said. “So sometimes there are agencies that are just going to be a little slower to get with the program, and I think that’s obviously where relationships are very important. I tell people all the time that we’re in a relationship business, and that’s one of the reasons that when I have a new agency head that I’m dealing with, I immediately try to schedule time to talk and start to develop a relationship so that they understand where I and NTEU are coming from.”

Bumps In the Road Back to the Office

One of the common sources of public friction between federal employee unions and agency management during the Biden administration has been over how to bring employees who had been teleworking full time during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic back to traditional work sites.

Amid the backdrop of growing backlogs for services that traditionally been based primarily around in-person visits to agencies from taxpayers and outcry from mostly Republican lawmakers, agencies entered often fraught negotiations with their unions on reentry, while unions sought to ensure adequate safety measures were put in place for the return to office and protect employees’ access to telework, remote work and other workplace flexibilities.

Although there were some outlier cases where agencies skipped the collective bargaining process required ahead of announcing reentry policies, like at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, union leaders said that by and large, it was a difficult yet productive process.

“With the understanding that so many of our employees never left the office—and I think there was a misunderstanding in the media world that all of the government went home [due to COVID] and they didn’t—we have been trying to get agencies to negotiate a safe, working return for those that were working remotely, and I think we finally were able to get there,” AFGE’s Kelley said. “But we’ve also had a lot of success in securing expanded telework at agencies like the Education Department, EEOC, and [the National Science Foundation]. Making sure those that have to return to the office return in a safe manner is vitally important to us.”

Reardon suggested some of the difficulties in negotiating reentry agreements stemmed from just how granular the talks were, from the amount of telework that would be permitted after employees return to how the agency would schedule when each phase of the process would begin.

‘We had some agencies that were very open to return-to-office negotiations and working really well with us, and you had others that were not quite as interested,” he said. “What it often came down to was things like telework or the actual date or how that return was actually scheduled, and there were a lot of different reactions we got from agencies on that. But I think on the whole, we were pretty successful.”

And Biggs said that despite the calls from lawmakers to bring employees back to work en masse, he believes the pandemic actually helped labor groups make the case to maintain a higher level of telework than was available prior to 2020.

“It was unprecedented, with the pandemic, the amount of working from home and teleworking, but I think that ultimately greased the skids, if you will, for creating an environment where they do have to sit down and discuss how it’s going to be implemented,” he said.

Agencies and unions alike are likely to encounter more resistance to expanded telework and other workplace flexibilities from the newly divided Congress. House Oversight and Accountability Committee Chairman James Comer, R-Ky., announced last week that he has introduced legislation that would require agencies to revert to pre-pandemic telework policies as well as a study about how telework impacted government services and productivity.

Expanding the Union Tent

In addition to rolling back Trump-era policies targeting union activity in the federal government, the White House has recommended a number of measures to make it easier for federal employee unions to communicate with workers they represent, as well as expand into agencies whose workforces have historically remained unorganized.

OPM last year began including new capabilities in its FedScope database of federal workforce information, allowing users to search based on employees’ union representation, including the ability to see which agencies have workforces that are eligible to organize but have yet to do so.

Those measures have bolstered preexisting efforts by labor groups to both organize new bargaining units in underserved agencies, as well as boost union density within longstanding bargaining units, union officials said.

Kelley said that for 14 of the last 15 months, AFGE has met its monthly goals for attracting new members. He suspects that at the root of that growth has been the union’s successful advocacy for legislation and administrative actions that have tangibly improved employees’ lives, like the 4.6% average pay raise earlier this month and better pay and expanded collective bargaining rights for Transportation Security Administration employees.

“The 2023 omnibus spending bill, which allotted $198 million to improve the pay of TSA officers, and Administrator [David] Pekoske’s determination that expanded collective bargaining rights, these things all help in organizing,” he said. “The return to a one-year probationary period for Defense Department employees, this will help us in organizing. When you think in terms of the Education Department, with the four-year battle to repeal the anti-union contract [imposed under Trump], refund lost union dues restore payroll deductions, and make whole employees who were disciplined or otherwise incurred hardships, these all will help us to continue to organize.”

Last year, employees at the Bureau of Land Management’s headquarters voted overwhelmingly to unionize and under the umbrella of NTEU, following similar success at its New Mexico regional office in 2021.

And AFGE saw nearly 30 of the 34 union-eligible employees at the Institute of Museum and Library Services vote in favor of organizing last November, while 125 Millennium Challenge Corporation workers will vote Wednesday on whether to unionize. Peter Winch, an AFGE staffer who guides federal workers interested in unionization through the process, said the IMLS vote marked an encouraging change in how unionization efforts typically progress.

“I think we had 34 bargaining unit-eligible employees, and 20 of them signed the showing of interest and then 24 votes, but then we had even more than that sign up as members, something like 28 or 29,” Winch said. “In the old days, you would struggle to get the showing, and then hope that they all vote to organize and then become members, but we’re actually increasing our support at every one of these turning points.”

Reardon said it’s too early to say, but he suspects the renewed momentum behind unionization could reflect broader trends in favor of labor in the American economy. In recent months, employees at Starbucks, Amazon and in the video game industry have engaged in high profile, and frequently successful, fights with their employers to form unions.

“We are certainly seeing an increase in membership, and one of the ways to really look at it is through the newer members at IRS, because they’re undergoing such a big hiring spree,” Reardon said. “As these new employees are coming in, we’re seeing a pretty significant surge in our number of members. Are we seeing these folks coming in now interested in us because of what’s happening in the larger labor movement, or is it simply because they’re coming into an environment where membership is already pretty good? I don’t know the answer, but what I do know is that they’re joining.”

Reardon also suggested that the tumult of the Trump administration has taught unions, after years of declining membership and power, how to sell themselves to employees.

“One of the lessons we as an organization have really learned is to show our work,” he said. “We’ve always done a really great job of making things happen, but I think sometimes we were too quick to get on to the next issue and try to win on the next thing, and we didn’t often take the time necessary to celebrate the win. And even when you don’t win, we need to tell our members what we’ve done in the fight and why. Because those are a couple things that are central to what members want: They want you to fight and to care about them.”